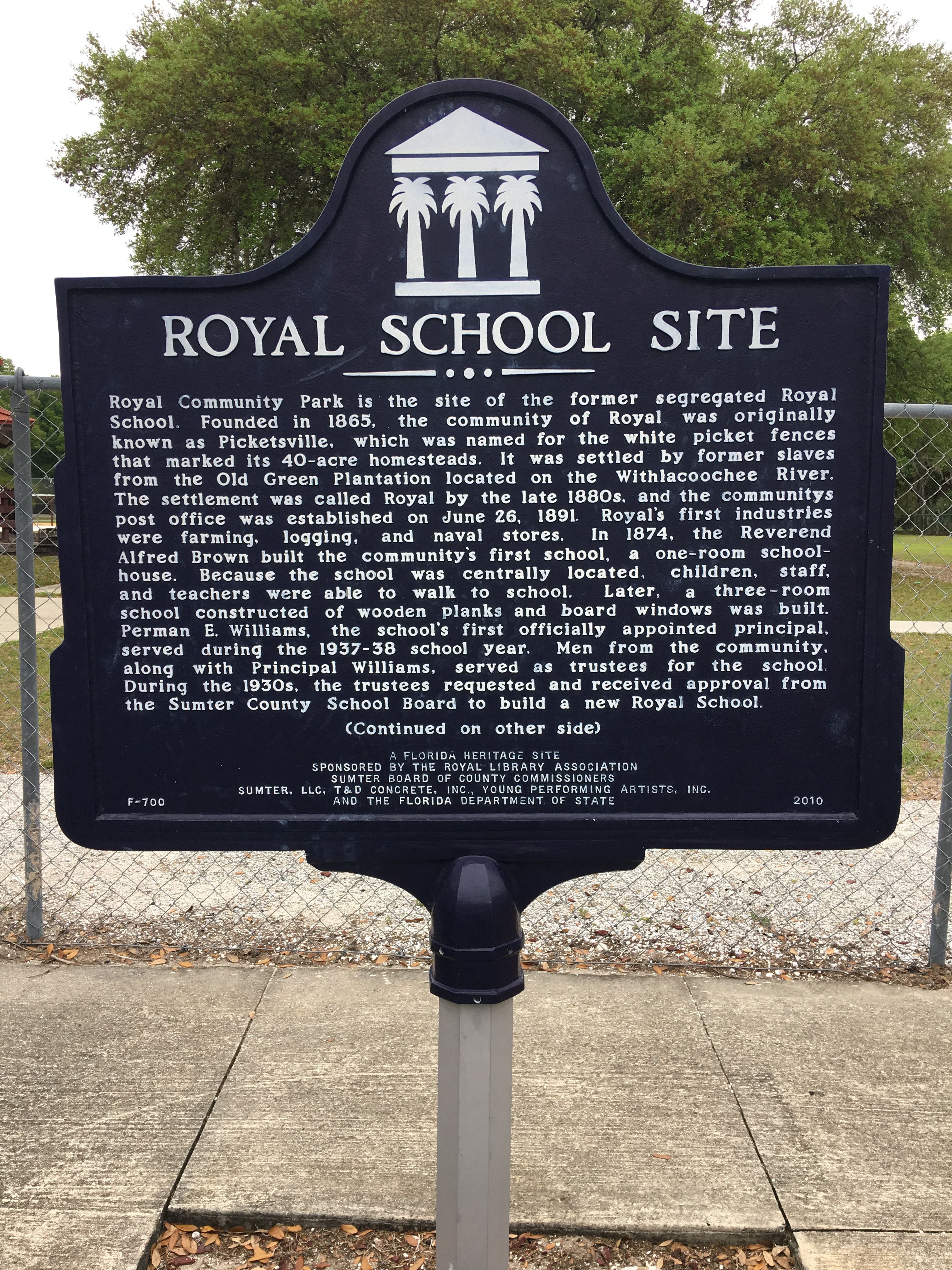

I joined thirty ladies of the National Society of Daughters of the Union on a field trip to Royal, one of Florida’s oldest African American communities, fifteen minutes’ drive from The Villages, Florida. We drove up to a fenced area with an historic marker commemorating the Royal School Site. The school no longer exists. Structures on the ground include a beige concrete building that once housed the last school cafeteria, and now used as an enrichment and historical center. Another building contains a kitchen and a large cafeteria. Between the two buildings stands an outdoor wooden gazebo for use during picnics. Behind these structures is a playground and tennis, badminton area. Everything is well maintained and for the use of the community.

Karen Carbonneau, Regent of the Brigadier General Truman Seymour Chapter of the National Society Daughters of the Union officiated a short meeting welcoming two new members and presenting a certificate and donation to Beverly Steele, Founder of Young Performing Artists (YPAs), Inc. the corporation who owns the center.

Ben Simmons, a professional vocalist who works with YPAs, Inc., serenaded us during our lunch of baked chicken, great northern beans, perlo rice, cornbread, and 7up cake. After lunch, we returned to the beige concrete building where Steele led us into a small history room.

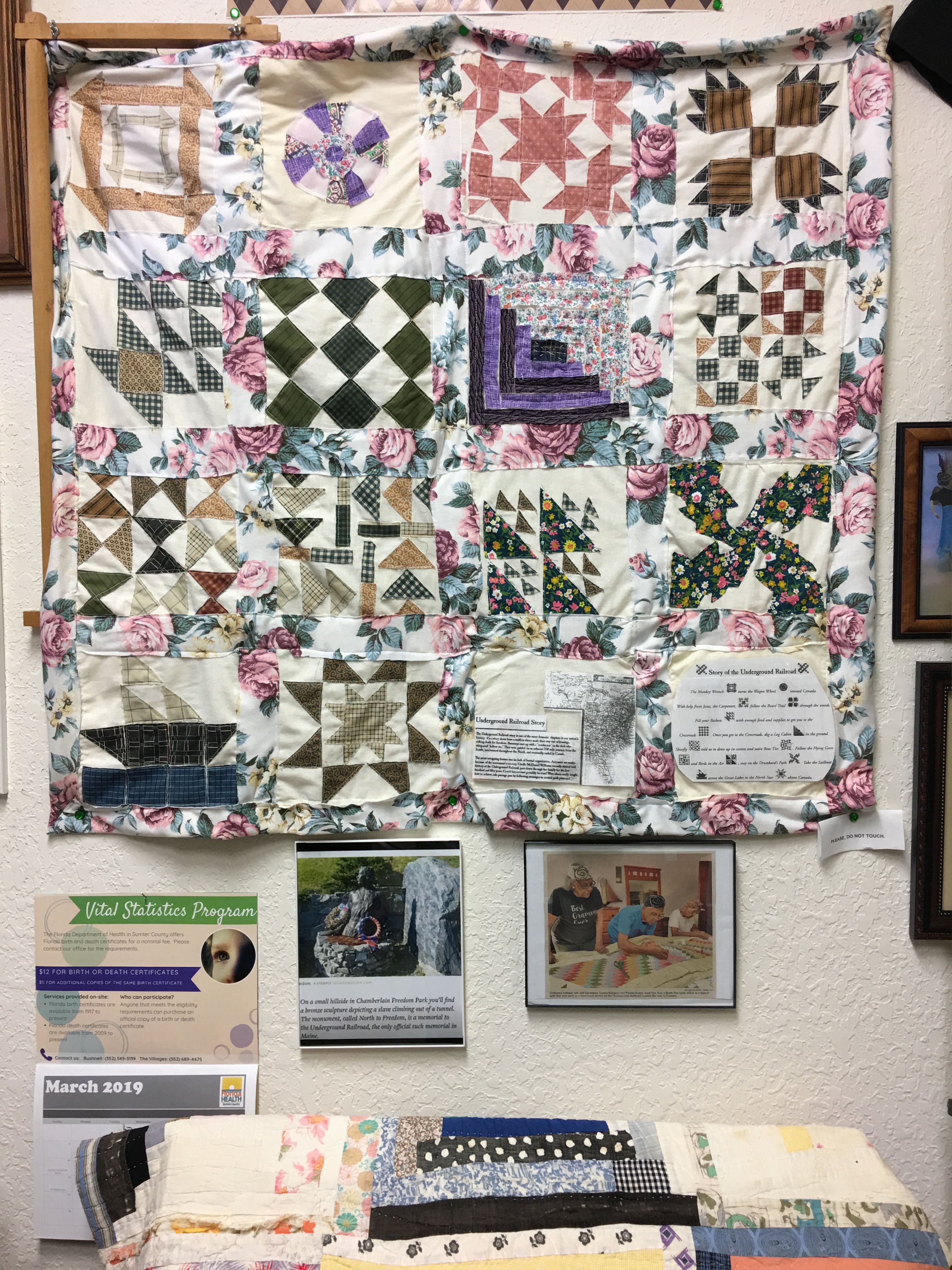

African American history came alive when Steele talked. She spoke about the Underground Railroad and explained an unusual quilt hanging on the wall. How did Harriet Tubman and other escaped slaves find their way through the Underground Railroad to freedom in Canada? This quilt held the answer.

As Harriet or other leaders (conductors) led these slaves (passengers) following the drinking guard (the North Star) to specific safe houses (stations), signs appeared in nature or on quilts. As they passed various places, symbols sewn on this quilt told the conductor where to go. Often these quilts appeared on the window or over the porch railing. Abolitionists left food and clothing for the passengers.

Steele read the quilt to us while pointing at each block symbol: The Monkey Wrench turns the Wagon Wheel toward Canada with help from Jesus, the Carpenter, follow the Bear’s Trail through the woods. Fill your baskets with enough food and supplies to get you to the Crossroads. Once you get to the Crossroads, dig a Log Cabin in the ground. Shoofly told us to dress up in cotton and satin Bow Ties. Follow the geese and birds in the air, stay on the Drunkard’s Path. Take the sailboat across the Great Lakes to the North Star Canada.

Steele’s entertaining stories left an imprint for understanding the plight of early slaves and their struggles after freedom. Before the Civil War, escaped African men and woman and children lived with the Seminole Indians, in the Pilaklikaha or the Long Hammock areas. Many did not mix with the Indians and maintained their pure African heritage. Others did mix. These part Indian and part Negro people were labeled Mulatto. Often the white master of a plantation took one or several slaves as his, creating mixed- blooded children of White and African heritage. These children lived with the slaves but were often educated and given a little land upon the master’s death. They, too, were termed, Mulatto.

Liberated slaves had nowhere to go and no skills. They owned nothing. Most could not read nor write. Many followed the Union soldiers and were given some food, but soon they became a burden. On January 16, 1865, General Sherman issued Special Field Order 15. This order provided 40 acres of land, confiscated from or abandoned by plantation owners, and a mule for plowing. Many slaves simply left their former homes in search of family members who had been sold, while others, marked off their 40-acre homesteads.

The assassination of President Lincoln left Johnson in charge. President Johnson and General Sherman didn’t get along, so Johnson revoked Special Field Order 15. Many Blacks who had settled elsewhere lost their land and became sharecroppers for the original plantation owners.

This community’s first settlers were former slaves from the Old Green Plantation located on the Withlacoochee River. The first settling families were the Harleys, the Andersons, and the Pickets. They marked off their forty acres with white picket fences, built log cabins and dug wells for water before plowing and planting.

Before the Civil War, the Long Hammock settlement of Blacks had first been quietly known as “Royalsville.” Had the slaves in this area been African Royalty? For a time after the war and with the influx of free slaves, Royalsville became known as Picketsville. But residents wanted their royal ancestry known, so by the late 1880s early 1890s, Picketsville, quietly, became known as Royal. The town was documented as Royal in 1880 and a post office established in 1891.

Today, Royal is a community, rather than a town. It is not part of the nearest city called Wildwood. Its population stands at 2205. Slowly few of the present-day heirs to this land, sell. But there is a significant number of families who trace their lineage to freed slaves who were originally given the land under Order 15. Many families work elsewhere while maintaining their forty-acre lots. The children attend Wildwood Elementary, Middle and High Schools.

This brief outline of African American History spoke louder to me than any I had taught or learned from history textbooks. Having this community heritage center brings history alive to the people of Sumter, Marion, and Lake County. To top it off, we left this area with a small brown paper bag containing a dab of fresh homemade elderberry jelly and a freshly

baked biscuit.

baked biscuit.

baked biscuit.